In this article, you will learn all the basics there is to know about athletic performance, both for you and your pupils. There are many different schools of thought, each with their own ideas on how to train athletes to increase athletic performance. So how does one know that that particular program is going to work for any given athlete? The training principles are a group of components that have been scientifically proven to increase performance. They can guide coaches to ensure their athletes get the maximum benefits from their training regimen.

Overload principle

The first principle is known as the principle of overload, it is summarized in the following quote: “For any component of fitness to improve, it must be overloaded. To obtain optimal improvement and prevent injury, overload must be individualized and progressive ”(Hodge, Sleivert, McKenzie, 1996). Most athletes can relate to this principle anecdotally. They are aware that if they don’t push themselves a little harder in training, they won’t see performance improvements in their chosen discipline.

The principle of adaptation is important because the body adapts to everything by obtaining a series of responses that seek to satisfy the requirement of the increased workload. These adaptations vary depending on the type of training performed. For example, resistance training can increase blood volume, blood oxygen transport, and capillary density in trained muscles (Reaburn and Jenkins 1996). Weight training can lead to adaptations, including increases in muscle fiber size, lean body mass, ligaments and tendons, strength, and creatine and myokinase enzyme activity (McArdle, Katch, & Katch, 2001 ).

This is why progressive overload is necessary. By continually increasing the amount of overload, the body will continue to adapt, allowing for greater gains. There are a number of ways to ensure that this overhead is achieved. The FITT (Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type) principle brings all of this together (Hodge, Sleivert, McKenzie, 1996). There are four key factors that can be manipulated to achieve overload. Are:

- Frequency: The number of training sessions per week.

- Intensity: How strong the physical activity is being, reflected in some measures such as heart rate, the level of perceived exertion, or a measure like maximum repetition (for example, 8 RM).

- Time: Measured differently depending on the type of exercise that is performed. Aerobic work is typically taken as the total amount of time per session, as well as the applicable distances, while with weight training volume, the number of sets and repetitions performed are often recorded. The amount of time the individual has been exercising is also often measured to ensure that the targeted energy system is being used (for example, 5-10 second intervals of exercise load short-term energy systems. anaerobic phosphagen, the 20-60 second intervals load the anaerobic system lactic acid, and the intervals of more than two minutes mainly load the aerobic system).

- Type: The type of fitness components trained and exercises performed. This is the basis of specificity.

Specialty Principle

The following principle is the principle of specificity: “The characteristics of a training load must be specific to the movement, muscles and energy systems used by the sport for which you are training” (Hodge, Sleivert, McKenzie, 1996 ). Types of specialization (Cochrane 2005) include:

- Energy systems specialization.

- Training mode specialization.

- Muscle group specialization and movement patterns.

- Posture specialization.

This principle confers that one should try to keep all one’s training as sport-specific as possible, regardless of the type of fitness being trained. The only exception to this is when injury or the possibility of injury limits the athlete from specific training. In this case, the exercises should be as specific as possible while mitigating the risk of injury. Many athletes focus on this principle when they see it reflected in their performance and reviewing the type of training and exercises used before the event.

Eugene Coleman (2002) summarizes this, stating that: “Know what you need and train to achieve it. You need to lift weights to get stronger, run to be faster, and run, hit, catch, jump, and throw to become a better athlete. If you are going to spend 80% of your time jogging, you are going to practice being slow ”.

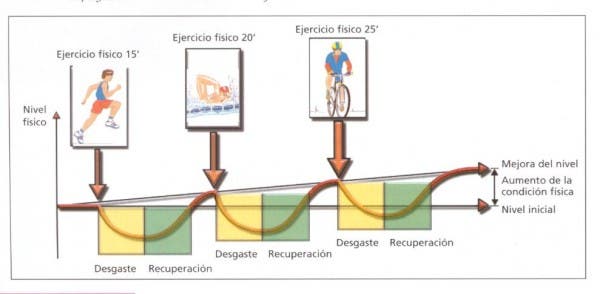

Rest / recovery principle.

The rest / recovery principle clearly states that adequate rest is necessary to maximize improvements in physical fitness. Rest should be considered, not only between daily workouts, but also by scheduling rest / recovery weeks along an annual training plan. Rest doesn’t just mean sleeping in late and avoiding all physical activity, although sometimes this is an option! Instead, the focus should be on active recovery sessions that involve activities such as massages, stretching, sled dragging, low intensity / low volume workouts, and hydrotherapy. Most professional athletes have felt the signs and symptoms of overtraining and should be acutely aware of the need to monitor for these symptoms, as well as plan training sessions to avoid them.

Coleman (2002) comments, “No matter how hard you work, you don’t make a profit during workouts. Gains are made during payback periods. Recovery is one of the most important and most ignored principles of training ”. Many coaches attest to this after watching their inexperienced athletes wrestle through hours of training six days a week with very little benefit. These athletes can also benefit from learning about the recovery principle… and recognizing that more is not always better! ”

Tuning principle.

The taper principle is, in essence, a period of time during which training is steadily tapering off to allow maximum performance in the actual event. This taper should be approximately two weeks in length just prior to competition, and by gradually reducing the training volume while keeping the intensity at the competition level, a performance increase of up to five percent can be achieved ( Hodge, Sleivert, McKenzie 1996). This concept is well known and widely used in strength sports. This is reflected in an old weightlifting saying, “There is no point leaving your best lifts in the gym.”

Individualization and ceiling principle.

The principle of individualization and ceiling is important when considering how to maximize the improvement of a skill and the level of performance of an athlete. The key aspects of this principle is that athletes will benefit most when programs are planned to meet their individual needs and when the capabilities of the individual are taken into consideration. Individuals respond differently to training. Some get “good” answers and some are “bad” answers. As such, programs may need to be adjusted to reflect the needs of the athlete (Hodge, Sleivert, McKenzie, 1996). Many athletes take notice of this after they have seen training partners get huge performance gains, while they only progress slowly. This situation may indicate that changes should be made to both athlete programs.

This principle also considers the amount of time an athlete has been training and how close they are to their individual genetic potential (their ceiling). Many athletes can recall times when they added an extra 20 kilograms to their bench press in just two months or the year when they cut their best 100-meter time by 1.2 seconds. These rapid gains in overall performance occur during a relatively early phase of an individual’s training. These gains will gradually decrease as time passes. This principle considers that an athlete close to his “ceiling” in one type of physical quality can benefit from improvement in another physical quality. An example of this is a team sports athlete whose speed is reaching its peak. However, with work to improve flexibility, this athlete could increase overall performance on the field, as well as reduce the risk of injury. Coleman (2002) discusses the development of the total athlete by stating: “You can’t go far by being strong or fast or flexible or skilled. You need the whole total-physical package. “

Principle of reversibility or detraining.

The next principle is the reversibility or detraining principle. Simply put, this is the “use it or lose it” principle. Most athletes who have been out of training for a long time recognize that their performance decreases if the body is not continually overloaded. This is evident in the gym when training has been neglected for an extended period. Once-easy weights seem unusually heavy, and the soreness is the highest of all time for the next week. The body clearly reverses its adaptation of increased strength and decreased recovery times. This principle has a silver lining however. Untraining can allow an athlete to recover physically and psychologically from long periods of training, allowing them to return to training with renewed enthusiasm.

Obviously not all athletes can train at a high level all year round. So how can they prevent the detraining effect? This is where the last principle, the maintenance principle, comes into the equation. To maintain the gains in fitness for periods of up to three months, an athlete can manipulate the FITT principle already described above and allow the training frequency to decrease by up to two-thirds (Cochrane 2005). This principle is often used effectively by athletes whose sport involves well-defined seasons that do not allow the level of training achieved in the preseason to continue while competing (See the case of soccer, the calendar allows during the summer break to reduce the frequency of training sessions until they are almost eliminated, to later regain performance during the start of the season).

So how do all these training principles fit together? Any training program must consider all aspects of the training principles in relation to the athlete for whom the program is written. A periodization model should be used, dividing the training year into phases to train the specific types of physical fitness necessary for the athlete. This plan should encompass the amount of overload on the athlete (using the FITT principle) and the amount of rest and recovery the athlete requires. Both overload and rest should be adjusted to maximize the athlete’s adaptation to the training stimulus. The program must determine where and how the set-ups will be used to allow the athlete to reach a competition at their peak levels. Maintenance training and / or detraining periods can be used throughout the year, but their use is limited to seeking the maximum benefit for the athlete. A coach must work very closely with his or her athletes, following and adjusting their training as necessary. If an athlete approaches his performance potential (“ceiling”) in one physical quality, the coach may consider modifying the plan to obtain more benefits from the increase in other types of qualities.

In summary, training principles are essential for coaches and athletes who want to get the most out of their training and avoid the “trial and error” approach often used by some coaches.

Written By: Nathan Williams for EliteFTS.

Translated by: Arturo Cantarero.